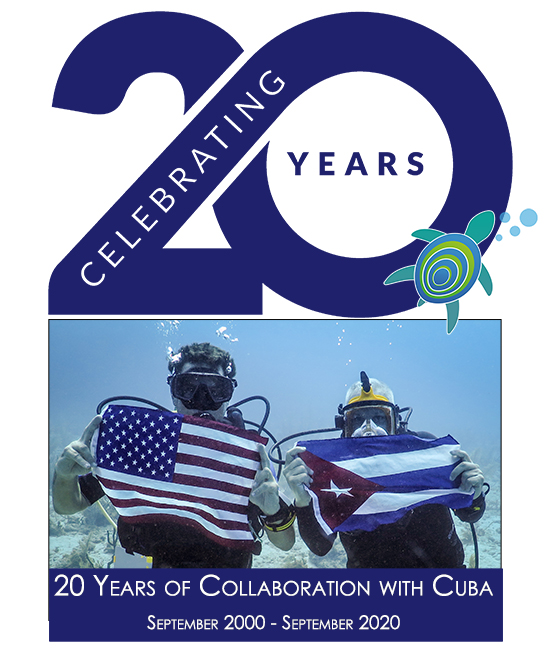

My 20 Years in Cuba

Today I celebrate 20 years working in Cuba side-by-side with an extraordinary group of Cubans dedicated to science and conservation. In September 2000, as Vice President for Conservation Policy at the Ocean Conservancy, I took my first of what would eventually be 106 journeys to Cuba, completely unprepared for what I would experience, an island seemingly defying time, both above and below its coastal waters.

Even today, Cuba seems to be caught in a unique time storm, with relics of a century past coexistent with early 21st century modernities: Horse-drawn buggies stopped at a traffic signal alongside modern Hyundai sedans; sixty-year-old rotary phones still in regular use alongside shiny new iPhones. It is disorienting to travel through an island where so much is still frozen almost as it was more than a century ago, with more than half of century of isolation and an an ongoing economic embargo from its nearest neighbor, the United States.

A Living Time Machine

Little did I have any inkling when I first set foot on this exotic island what lay in store over the next two decades. I underestimated everything, from this island’s relentless gravitational attraction that would pull me back time after time, even after I had given up hope of succeeding there. Nor did I appreciate what difference I could possibly make, a Jewish kid born in Philadelphia without a drop of Latin blood in his veins and little memory of the Spanish he had struggled with during his undergraduate studies decades earlier. But I would soon discover – and treasure – my newfound Cuban soul. At one point the former president of the Dominican Republic wagged his finger at me after a speech I gave in Santo Domingo, telling me that I speak Spanish with a strong Cuban accent. I took it as a great compliment.

Little did I have any inkling when I first set foot on this exotic island what lay in store over the next two decades. I underestimated everything, from this island’s relentless gravitational attraction that would pull me back time after time, even after I had given up hope of succeeding there. Nor did I appreciate what difference I could possibly make, a Jewish kid born in Philadelphia without a drop of Latin blood in his veins and little memory of the Spanish he had struggled with during his undergraduate studies decades earlier. But I would soon discover – and treasure – my newfound Cuban soul. At one point the former president of the Dominican Republic wagged his finger at me after a speech I gave in Santo Domingo, telling me that I speak Spanish with a strong Cuban accent. I took it as a great compliment.

Neither had I anticipated that I would be swept away into a journey though time that I can still barely believe, one that would bring me face-to-face with vibrant, healthy coral reefs even healthier than the spectacular ecosystems I remember from the early seventies in the Florida Keys, reefs that were the inspiration of my career in marine science and conservation, reefs that would soon succumb to a tidal wave of humanity invading Florida’s shorelines. And so would go much of the Caribbean. The coral reefs my colleagues and I had so cherished in the seventies are 80 to 90 percent dead. In the rest of the Caribbean, the figure is roughly 50 percent.

At a time when I had come close to giving up hope for corals in the same way that many conservation groups abandoned the Caribbean as a lost cause, Cuba came to my emotional rescue. Just like the dazzling carpet of schoolmasters, grunts, tang and parrotfish spilling over the mustard walls of Florida’s Looe Key so transfixed me that summer in 1974 as a young teenager, so did my eyes widen and my heart race with joyful disbelief as I slipped below the surface into an underwater paradise as frozen in time as the rest of Cuba, taking me back for a few precious minutes — as long as the tank on my back would reward me with another breath — to those magical days of vibrant reefs and the inspirational thought that learning from Cuba’s “living laboratory” could offer the rest of us a second chance to do things right.

I beheld magnificent stands of healthy elkhorn coral, teeming with colorful grunts, snappers and angelfish. I came face-to-face with Goliath groupers, a critically endangered species, more than triple my weight. I found myself surrounded by dozens of healthy Caribbean reef sharks, silky sharks, tarpon and myriads of other vibrant fish and corals, all the while seeing no evidence of the decay and disease the rest of the Caribbean had suffered over the past half century to protect their coral reef ecosystems.

I beheld magnificent stands of healthy elkhorn coral, teeming with colorful grunts, snappers and angelfish. I came face-to-face with Goliath groupers, a critically endangered species, more than triple my weight. I found myself surrounded by dozens of healthy Caribbean reef sharks, silky sharks, tarpon and myriads of other vibrant fish and corals, all the while seeing no evidence of the decay and disease the rest of the Caribbean had suffered over the past half century to protect their coral reef ecosystems.

Two Decades of Accomplishments

One of many joint expeditions to create the first ecosystem maps of Cuba’s Gulf of Mexico waters and in the process, help train the next generation of Cuban marine scientists

This month I’ve been reflecting on the many accomplishments we’ve been able to achieve despite maddening bureaucracy, ever-changing political relations, and emotional states regularly oscillating from euphoria to despair and back all along the way:

- We have supported research of the waters we share with Cuba. I am proud to have supported and participated in a decade of expeditions which, for the first time, created ecosystem maps of Cuba’s northwestern coast. Our work has led to the publication of dozens of peer-reviewed scientific papers and has helped advance conservation efforts in Cuba.

- Equally important, our work has helped train the next generation of Cuban scientists, supporting the Master’s and Doctoral theses of dozens of students at the University of Havana’s Center for Marine Research, the only institution in Cuba where marine scientists are accredited. Today those students are the leaders of marine science in Cuba, one of whom went on to direct the center.

- At Ocean Doctor we have moved from pure research to the hard work of solving problems. We’re working with our Cuban colleagues to apply the tools of environmental economics to create solutions for small coastal communities with few economic opportunities, providing them with incentives to protect — not destroy — their coastal ecosystems. We’ve led efforts with colleagues at the Cuban Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment, World Resources Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, University of Colorado, Boulder, and The Baum Foundation to hold several workshops to develop new strategies to address such challenges. Thanks to your support and that of the Ford Foundation and others, we have been able to continue this important work up to today.

- Our landmark report, A Century of Unsustainable Tourism in the Caribbean: Lessons Learned and Opportunities for Cuba, produced in collaboration with the Center for International Policy and attorney Robert L. Muse, has educated thousands about the devastating environmental track record of mass tourism in the Caribbean and the extraordinary opportunities Cuba still has to avoid such mistakes.

- In collaboration with the former Chief of Mission of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana under President Jimmy Carter, Wayne S. Smith, along with attorney Robert L. Muse, considered the foremost expert on Cuba and U.S. law, and our colleagues in Cuba, I co-founded and led the Trinational Initiative for Marine Research & Conservation in the Gulf of Mexico and Western Caribbean with the goal of elevating collaboration to a new level.

-

Dr. Fabián Pina, former director of the Cuban Center for Coastal Ecosystem Research (L), Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (Center) and myself (Right) at the State Department continuing our work to develop a blueprint for U.S.-Cuba collaboration in marine science which laid the foundation for the first agreements between the U.S. and Cuba

In 2014, months before there was an inkling that relations between the U.S. and Cuba were on there way to normalization, we brought marine conservation leaders from Cuba to Washington, DC where we organized a meeting with members of Congress, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. State Department, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Cuban Ambassador, the head of U.S. relations from the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Relations, to develop a plan of how the two countries could work together to conduct research, conservation and even establish a shared ocean “peace park,” a joint protected area at sea.

- After relations began normalization in late 2014, the first two memoranda of collaboration between Cuba and the U.S. were on the environment, building directly from those plans.

- Collaboration between the U.S. and Cuba on the marine environment has been singled out as one of the best examples of meaningful and enduring collaboration between the two countries. When I attended the emotional reopening ceremony of the Cuban embassy here in Washington, diplomats extended their hand to thank Ocean Doctor and the other environmental organizations working in Cuba for helping lay a foundation of trust and friendship that helped advance the normalization effort. “This wouldn’t have been possible without you,” more than one told me.

- Our work has drawn the attention of the media with feature stories by 60 Minutes, NPR, PBS NewsHour and the New York Times among many others. Such exposure has helped millions see another side of Cuba and appreciate the importance of U.S. collaboration with Cuba.

- Over the years I have helped introduce numerous U.S. organizations to Cuban institutions and to help build their research and conservation programs in Cuba, including the Ocean Conservancy, Mote Marine Laboratory, the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, The Ocean Foundation and Eckerd College among numerous others.

- Ocean Doctor has also had the privilege of introducing hundreds of you to Cuba through our Cuba Educational Experiences Program where you have met with Cuban environmental leaders, learned about Cuba’s environmental successes, challenges and opportunities, dove beneath the country’s beautiful waters, and most important, experienced the incredible warmth of the Cuban people.

Unprecedented Challenges

Today we face unprecedented challenges in our work, brought on by chilled relations between the U.S. and Cuba and, of course, by the pandemic. My heart breaks for my Cuban colleagues who depended on tourism for their livelihood, who can’t afford food and medicine and face an uncertain future.

For Ocean Doctor and other nonprofit organizations working in Cuba, the faltering U.S. economy and deteriorating relations with Cuba has meant a precipitous drop in foundation funding. Our travel program, another important source of financial support, has been suspended during the pandemic. We therefore need your support to allow us to continue our important work in Cuba. I am deeply grateful for your stalwart support over these years and ask you today to consider a donation of $20, one dollar to commemorate each year I have worked with our Cuban colleagues to make a difference for both Cuba and the U.S. If you’re able, a $200 donation ($10 to commemorate each year) or a donation of any multiple of 20 would be used directly to support Ocean Doctor’s Cuba Conservancy program.

For Ocean Doctor and other nonprofit organizations working in Cuba, the faltering U.S. economy and deteriorating relations with Cuba has meant a precipitous drop in foundation funding. Our travel program, another important source of financial support, has been suspended during the pandemic. We therefore need your support to allow us to continue our important work in Cuba. I am deeply grateful for your stalwart support over these years and ask you today to consider a donation of $20, one dollar to commemorate each year I have worked with our Cuban colleagues to make a difference for both Cuba and the U.S. If you’re able, a $200 donation ($10 to commemorate each year) or a donation of any multiple of 20 would be used directly to support Ocean Doctor’s Cuba Conservancy program.

On today’s anniversary, as I look back on the twenty years that have passed, I recognize that the experiences I had in those early years in Cuba were so powerful that they would inspire some of the most important work of my career. But they would also leave me humble and speechless, groping for adjectives that don’t exist, reminiscent of explorer Meriwether Lewis’ emotional encounter with the Missouri Falls in 1805, excitedly describing it in his journal as “the grandest sight I ever beheld.” After rereading his words, however, he scrawled his exasperation and despondence in a rambling apology to the reader, punishing himself for offering words that so inadequately conveyed the grandeur of the wondrous sight he beheld. I would spend years searching for the right words to describe coral reefs, but, as with Meriwether Lewis, they continue to elude me.

Sincerely and with gratitude,

David E. Guggenheim, Ph.D.

Founder & President