Alone in the Dark with a Pen Light

Yesterday (Thursday) morning, Michelle Ridgway and I descended in the twin subs for our expedition’s penultimate dive on Pribilof Canyon.Michelle’s lights shone as tiny pinpoints in the distant green as the light from above slowly vanished and the cold darkness of Pribilof Canyon enveloped us.I had a rare moment amid the descent’s harried series of checks and radio transmissions to reflect on where I was, and Michelle’s lights reminded me of how tiny we were, trying to comprehend an enormous, complex tapestry in the darkness armed with only a pen light. But on this dive, some of those complexities began to tell a story.

The welcoming committee of squid was there to greet us en masse, larger squid this time, more abundant, and more aggressive. They rocketed through the water faster than anything I’ve seen, passing millimeters from the front of the light, causing a startling bright flash against their light bodies, before deploying a cloud of brownish ink, spreading their tentacles to reveal a hungry beak, convinced that the light that had drawn them to the sub meant food was near. Some latched on a appeared to try to take a bite. Others gave a menacing dance, another blast of ink, and rocketed into the darkness. Still others appeared in pieces, casualties of my thrusters. It was squid madness, and it was fascinating, even comical to watch. But it also was a vivid reminder of the predatory prowess of these animals — a small fish wouldn’t stand a chance, but at least the end would come in the blink of an eye.

The bottom arrived at 1,052 feet and I landed on what appeared to be some sort of geologic stratification — unusual layers and grooves of sediment in parallel lines across my path. I then realized I was looking at a trawl “scar,” the deep ridges in the bottom made by the wheels of a trawl net dragged across the bottom. A wide swath of bottom appeared as if it had been plowed like a cornfield, overturned sediment neatly piled along the long groove. I remembered that Michelle had told me some of the trawls used in these parts are as wide as a Boeing 737’s wingspan.

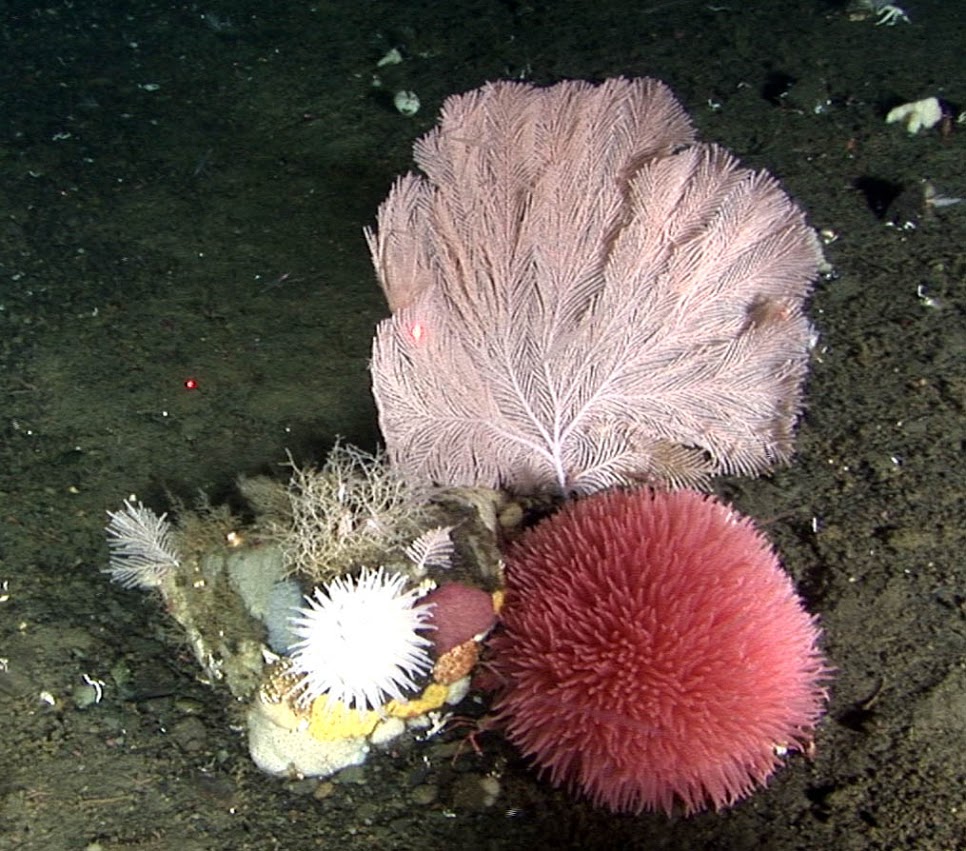

We began our transect, but shortly thereafter I was told to hold position — apparently the squid had won the last round against Michelle, causing one of her thrusters to blow a fuse. She surfaced for an early recovery while I continued the dive alone. I was excited to see a number of corals. The bottom was covered with tiny (an inch or two) white sea whips (Halipteris willemoesi), one of the corals we had seen elsewhere in Pribilof Canyon. But the sea whips we had seen elsewhere were much larger, 3 or 4 feet long. I only spied two or three that big in this location.

I moved along in the darkness, saw many snow crabs and flat fish, including the beautiful rex sole and equally dramatic sharp nose skate. I then spied a strange white ridge along the black horizon. As I approached I saw this ridge lay directly in my path, straight as an arrow. A geology professor of mine once gave our class a clue at identifying features in aerial photos by pointing out that straight lines are rare in nature. Sure enough, this was another trawl scar, larger than the first. I radioed to Sasha at the navigation station on the ship and asked that he note this location on his tracking computer. I continued and found many more linear features along my path, more trawling marks, no doubt, perhaps older ones.

As I continued ahead, some of the pieces I had been seeing in the tapestry during the week started to merge and suggest a pattern. Most of the tiny sea whips I had seen were roughly the same size, suggesting that they’re roughly the same age and most likely regrowth after a major disturbance, such as one that might be caused by dragging a massive object over the bottom…like a trawl. It’s gratifying to see an ecosystem demonstrating resiliency — little sea whips pushing up and trying to make a go of it. But knowing how important corals are to the health of marine ecosystems, it’s troubling to see such widespread impacts.

Continuing the transect, I enjoyed seeing the sole, halibut, skates and other flat fish. I’ve always been fond of these strange looking creatures and never appreciated the role they played in the tapestry until this dive. Shallow flat-fish-sized depressions cratered the soft bottom. But as I passed over these “flat fish holes,” the lights from the sub reflected off of hundreds of tiny eye balls looking back at me. These little depressions were teeming with little shrimp and other critters — colorful micro ecosystems moving in where a flat fish moved out.

This was an area of high current — maneuvering the sub was difficult — and I saw that these depressions offered the shrimp refuge out of the current on a silty bottom that was virtually devoid of rocks or other relief. I realized my flat fish friends were ecosystem engineers. The simple act of burying themselves in the silt and leaving a depression behind meant habitat for countless other creatures. NOAA scientist Bob Stone, aboard Esperanza for this expedition, smiled when I later mentioned this to him — he’s published a paper on the topic. I’ve seen a similar pattern in the Gulf of Mexico, where grouper dig enormous swimming pool-sized holes in the soft bottom sediment, exposing hard substrate for corals and sponges to grow and attracting many fish and invertebrates. So it’s troubling to me when we think of fish essentially as crops that we can simply harvest from the sea. Such a perspective ignores the critical point that fish themselves are part of the ecosystem and have important, often critical roles, in maintaining the health of the ecosystem. Removing fish from the ecosystem changes the ecosystem.

The call from Sasha came too soon, as it always does, “DeepWorker 6, at this time prepare the cabin for recovery.” As I ascended through the darkness, alone this time, I turned my lights off to gaze upon Pribilof Canyon in its true state and pondered how much of our planet’s life lives in complete darkness. My tiny sub had illuminated but a few new corners of this vast place. There lies so much more to see and discover, but with each tantalizing glimpse come new insights and a little more of the story the tapestry tells.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!