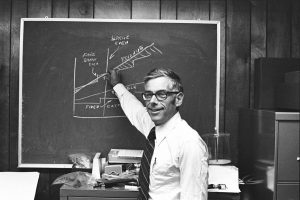

My father, William L. Guggenheim and his favorite fish, a Striped Bass caught off the New Jersey coast. (Photo: Ann Guggenheim, 1976)

November 28th, 1976 was a Sunday, marking the end of the long Thanksgiving weekend. I emerged from the subway surface trolley line in West Philadelphia to make my way back to my freshman dormitory at University of Pennsylvania, dreading the thought of my Spanish class at 8 AM the next morning. The day was a bit warmer than most recently, marking a break in the longest cold spell that year, 27 consecutive days of below-average temperatures. Yet the night air felt especially chilling and unsettled that evening. My phone was already ringing as I entered my tiny, dank dorm room.

“Your father isn’t home yet.” It was my mother. “He always calls me after he gets back to shore and he still hasn’t called.”

My mother, Ann, was a champion worrier, so my instincts were dismissive. My father had gone fishing off Cape May, New Jersey on our 23-foot Seacraft. He had invited me to go. I loved fishing with my dad, something we had shared for years. But now an 18-year-old with changing priorities, I decided I’d rather spend time with my girlfriend. So he went alone, something he had done many times before.

I wasn’t worried. My dad seemed superhuman to my brother, Alan, and me. There seemed nothing he couldn’t do. He was a mechanical engineer with an unending array of projects in the basement, the constant smell of solder and turpentine signaling his passion for industry, problem-solving and creativity. If something broke in the house, he would toil throughout the night until it was repaired. The garage was filled with carcasses of old dishwashers, washing machines and other appliances which he harvested for spare parts. We regularly rescued old black-and-white TV sets from neighborhood trash cans and repaired them on the weekends. As a result, our family of four had seven television sets. Alan and I marveled at what he could do and to our delight, he let us help. He set up work benches for each of us so the three of us could toil away on electronics projects together.

“I’ll call the Coast Guard, Mom,” I said, more to appease her than from any deep concern I had. I hung up and called directory assistance for the number of the Cape May Coast Guard station, then dialed the number. When the officer quickly answered with an air of military authority, I felt sheepish and, I suppose like any teenager, a bit embarrassed to bother him with what I was certain was nothing.

“Yes, uh, my father was fishing off Cape May today and he’s overdue. The boat is a 23-foot yellow Seacraft, registration number DL –“

Before I could finish spitting out our boat’s registration number, the officer completed it for me, “111 Golf.” At first I couldn’t understand how he knew. The confusion was short-lived and I understood, even before he explained, “The ferry spotted it going in circles.” The Cape May-Lewes ferry, Twin Capes, spotted the boat near the number three approach marker to the Cape May Canal. There was no one aboard.

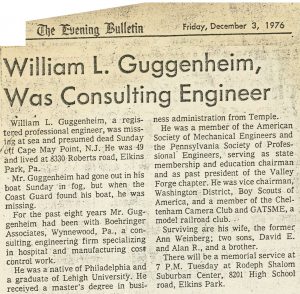

William L. Guggenheim grew up in the Philadelphia suburbs. He was a small-framed, athletic 5’7”. He was a skilled wrestler in college, but had to avoid most outdoor athletic pursuits because of severe asthma. He loved dogs, his favorite being an enormous black Newfoundland. He earned his engineering degree from Lehigh University and a Master’s in Business Administration from Temple University. He was a brilliant engineer and helped open factories in Puerto Rico and designed infant care facilities at New York Hospital. But his talents were not simply those of a gifted engineer. His creative side was equally impressive. He designed and built an HO model railroad layout in our basement that was the envy of the neighborhood, with each building and train car built from scratch and intricately painted. He rebuilt a player piano from a heap of dusty parts and later reaped his rewards by singing along – off key – to music rolls well into the night. He was an incredibly skilled, award-winning photographer and taught Alan and I to shoot and develop prints in the darkroom he built in our basement. Alan and I are passionate photographers and videographers to this day and photography is an integral part of my professional life.

I journeyed by trolley, subway and bus back to our family home in Elkins Park in the Philadelphia suburbs that evening where my mother, brother and I departed on the two-hour drive to Cape May, three-across in the back seat, driven by close family friends. The night grew black and heavy rains soaked the Garden State Parkway as we ventured south. The Coast Guard had little news for us. The weather did not permit a helicopter search. The boat had been recovered. Later, I went aboard. The fishing line on the port side had been deployed. Surely he was trolling for his favorite fish: The mighty Striped Bass. Why hadn’t the starboard line been deployed? Perhaps he fell overboard when trying to set it? I found the depth chart recorder still running. Scrolling the paper chart backward over the hours I found sudden, dramatic spikes indicating shallow water of only a couple of feet. Surely this was one of our favorite fishing grounds, Prissy Wicks Shoal, a mile off Cape May Point, the peak of a channel that plunges more than 30 feet to the bottom of the Cape May Rips, a high current area that washes Delaware Bay around the Cape May peninsula into the Atlantic. The boat could have been pitching violently crossing the shoal. If he had been astern where the freeboard is low, setting the starboard line or the chum pot at that moment… I thought of the 40-degree waters of the Bay. Swimming a few feet would be a painful struggle. Swimming a mile…

Of all my father’s passions and talents, there was one that stood above the rest, that constantly tugged at his imagination, peaked his curiosity and stoked his passion: The ocean. He taught Alan and me to fish from the surf and the slippery algae-covered rocks of the jetties surrounding Cape May Point. He took us deep-sea fishing aboard party boats. Years later, we would rent small open boats to fish offshore. Inevitably, the poorly-maintained outboard engines on these boats would fail and resist all attempts to restart them. With no radio or signaling device – except for an oar with a t-shirt draped over it – we would slowly drift with the current for hours, waving our oar until rescued. I remember these as wonderful times, sharing an adventure with my father, as he taught me about the sea. “Always look for the birds,” he taught me. Sometimes we’d find ourselves in the midst of a noisy, hungry flock, diving for the bait fish on top as we dropped our hooks, finding weakfish (“weakies”) on top eating the bait fish, and larger bluefish below, feeding on the weakfish. It was a wild display of Mother Ocean in action.

Later my father bought our first boat and he approached fishing like the engineer that he was, using our depth finder to locate a hole over which we would anchor and pull out flounder after flounder. Seeing our success, boats anchored around us, but caught nothing, asking us what kind of bait we were using, how fresh it was, what size hooks? As our neighboring fishermen grew red in the face with frustration, we tried to conceal our smiles. He taught me how to navigate and use a compass, chart and radio direction finder. Perhaps unwittingly, he ignited what would become, like his, a lifelong passion for the sea. For my 15th birthday I begged my parents for scuba diving lessons, which I received, and took my first breaths of compressed air in a musty YMCA swimming pool in Abington, Pennsylvania. My life would never be the same after that night.

My mother, brother and our family friends returned to Philadelphia, leaving me alone in Cape May. I slept for a few hours on a bench at the Coast Guard station and awoke to fog. The ceiling was 300 feet – still too low for a helicopter reconnaissance. I found my father’s car and went to Cape May Point to patrol the beach. I was joined by my father’s boss who journeyed down and we walked together. The shoreline was isolated except for us. I knelt by a beautiful baby bottlenose dolphin that had washed ashore, dead, and gazed out to sea. I started to accept the inevitable.

The weather finally broke, but the aerial searches proved fruitless. While Alan and I comforted ourselves with fantasies of an abduction at sea by a Russian sub – needing such a talented engineer in the motherland – we knew it was time to accept his loss, despite the fact that he was still officially “lost at sea.” I delivered a eulogy at the local synagogue on December 7th. As I reflect on the words I wrote and delivered to a packed temple that evening, they were as much in defense of the ocean as they were in honor of my father. I desperately didn’t want my family and friends to condemn the sea. To be certain, she has taken many lives and has, at times, terrified me to my core. But for my father and me, she was a gift, a place of sanctuary where we could connect like nowhere else, a setting that allowed our curious minds to soak in the wonders of an ocean world and the miracles of life below. I could think of no better way to carry my father’s love of the ocean forward than to dedicate myself to it fully.

His body was never found. Exactly forty years later as I write this, I’ve not only lived most of my life without him, but a few years ago, I outlived him. My father was only 49 when he died. Now I understand how young that is. He accomplished so much but Alan and I know he was just getting warmed up.

Rereading his obituary today, I realize that my father and I shared another passion. He chaired the education committee of the Pennsylvania Society of Professional Engineers and served as vice chairman, Washington District for the Boy Scouts of America. I remember him teaching Explorer Scouts in our living room. After learning to scuba dive, I went to Seacamp, a marine science camp in the Florida Keys and learned about the wonders of coral reefs. I later taught there during eight summers, five of which heading up a Girl Scout program. I still relish the memories of young nine-year-olds shrieking through their snorkels with amazement the first time they put their face beneath the waves. Today, Ocean Doctor’s Educational Travel Program is leading student groups to Cuba, teaching them about marine science and how to monitor coral reefs. On my 50th birthday, I set out to reach all 50 states to teach students about the wonders of the ocean and careers in science. So far, Ocean Doctor’s “50 Years, 50 States, 50 Speeches Expedition” has reached 22 states, 1 U.S. territory and the District of Columbia and more than 21,000 students. There’s no doubt I’ve inherited my father’s passion for the transformational power of education.

The ocean is a special place to many of us. It can be a place for joyous play with family and friends. It can be a place of solitude and reflection. As we gaze upon its beauty, it sometimes seems to speak to us personally, as if we’re connected to something profoundly bigger than ourselves, something intensely alive, rich with beauty and mystery. It’s impossible not to think of my father when I’m on the water. As I closed my remarks at the memorial service, I spoke from the heart with words I hoped would provide comfort. I told them that at sea, you never really feel like you’re alone. As for my father, I’m sure he didn’t feel that he died alone.

David E. Guggenheim

November 28, 2016