A Fragile Empire: National Geographic Examines Threats to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

“A Fragile Empire” can be found in the May 2011 issue of National Geographic magazine on newsstands April 26 (Photo: National Geographic)

Earlier this year, World Resources Institute released its “Reefs at Risk Revisited Report” (featured on The Ocean Doctor Radio Show) which spelled out a rather grim future for coral reefs due to both local and global threats, should we fail to take action. One of the bright spots in its report was Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, which has fared better than many other reefs around the world and has in place strong protections and management practices. But even this massive and remote reef system isn’t immune from the impacts affecting coral reefs worldwide. In “A Fragile Empire” National Geographic Magazine (May 2011) writer Jennifer S. Holland explores the various factors that are threatening Australia’s monumental reef. From rising water temperatures, to bleaching, massive flooding and high levels of acidity, the reef is in danger of collapsing and the prospect for recovery is uncertain.

A warming climate is pushing corals against the upper limit of their thermal tolerance, evidenced by mass bleachings like the one in 1997-98. A 60-year decline in ocean phytoplankton — microscopic organisms that form the base of the food chain — may also be playing a role. Recent flooding in Australia washed enormous plumes of sediments and toxins far offshore to the reef tract. And now, thanks to increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, the oceans are becoming more and more acidic as more of this atmospheric carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater. As the oceans become more acid, limiting the ability of organisms, like corals and shellfish, to build their limestone shells and skeletons.

Featuring the incredible underwater photography of David Doubliet, “A Fragile Empire” National Geographic Magazine (May 2011) tells the story of a fragile empire on the edge.

“Reefs for me are places for solitude and thought,” says Australian marine scientist Charlie Veron, here admiring a garden of stony corals on the northern Great Barrier Reef. “But I know there is fragility in their existence. I fear what lies ahead.” (Photo: David Doubliet/National Geographic)

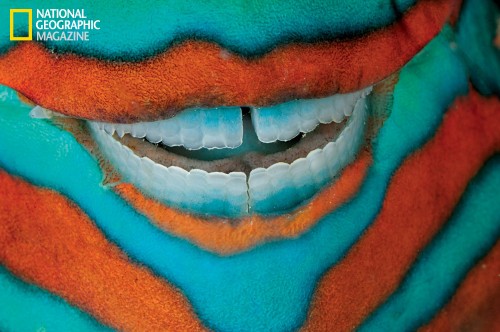

The clownish grin of a bridled parrotfish reveals its power tools: grinding teeth used to scrape algae from rock. Though sometimes destructive to individual corals, the fish’s efforts are mostly beneficial. Without them, algal growth could smother the reef. Scarus frenatus (Photo: David Doubilet/National Geographic)

Time and tides and a planet in eternal flux brought the Great Barrier Reef into being millions of years ago, wore it down, and grew it back — over and over again. Now all the factors that let the reef grow are changing at a rate the Earth has never before experienced. This time the reef may degrade below a crucial threshold from which it cannot bounce back.

– “A Fragile Empire” National Geographic Magazine (May 2011)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!